During the excavation of a more than thousand-year-old burial ground of Uelgi near Chelyabinsk, researchers discovered the remains of three men, one of whom died from blows to his head. Scientists learned what those looked like in life and suggested the circumstances of the nomads' death.

The history of the formation of the early Hungarian group (Magyars) begins in the South Ural region around the 8th century, probably with the merging of the steppe Turkic nomads (who had migrated mainly from the east to the west) with the Ugric, West Siberian and Ural population. However, the geography of the Magyar history is much more extensive: archaeologists have found traces of the ancient Hungarians in the territories from eastern Kazakhstan, Altai, the Kama region and the Urals to the Black Sea region and Transnistria.

The Carpathian Basin (historically – Pannonia; the territory of modern Hungary) of the second half of the first millennium AD is replete with artefacts of the same Kushnarenkovo and Karayakupovo archaeological cultures of the second half of the first millennium AD, typical of the South Ural Magyars.

In 2010, scientists from South Ural State University discovered the Uelgi burial ground (Kunashaksky District) in the Chelyabinsk Region, where more and more new finds have very close analogies to the belt set of the early Hungarians of the Carpathian Basin.

"These things have stylistic and decorative similarities. And these are not just, as they say, epochal things; such finds indicate that the South Ural region and Pannonia are connected," explained Ivan Grudochko, Associate Professor and Research Fellow at the SUSU Eurasian Studies Research and Education Centre. "Over the past ten years, our Hungarian colleagues have conducted a large comparative paleogenetic study (based on the analysis of bones from Carpathian burials and from the Uelgi burial ground). It has already proven, at an independent natural science level, that the ancient South Ural population has family ties with the early Hungarians from the Carpathian Basin."

The Uelgi burial ground is, first of all, an elite burial monument. According to researchers, about 80% of its human burials had been destroyed (possibly plundered) in ancient times. Among the things that can be found in abundance near Kunashak today are iron and bone horse harness items, belt sets, silver and gilded belt plaques, weapons, including a solid collection of sabres, which are considered early for the South Ural region of the 9th–10th centuries.

The features of the burial rite recorded in the Uelgi burial ground, as researchers note, are quite standard for early and medieval nomads: they had buried deceased people stretched out on their backs with their arms placed along the body. In some cases, the body had probably been tied up or wrapped in a shroud, as evidenced by the tightly packed bones.

The earliest Magyar burials discovered near Kunashak are distinguished by fairly deep pits for that era: up to 70 cm in the first half of the 9th century. Subsequently, in the 10th–11th centuries, such depths decreased, reaching about 15–20 cm.

In total, the Uelgi burial ground contains twenty-five mounds and one hundred and fifteen burials in varying degrees of preservation discovered to date. Not to mention numerous pits with remains that are difficult to identify.

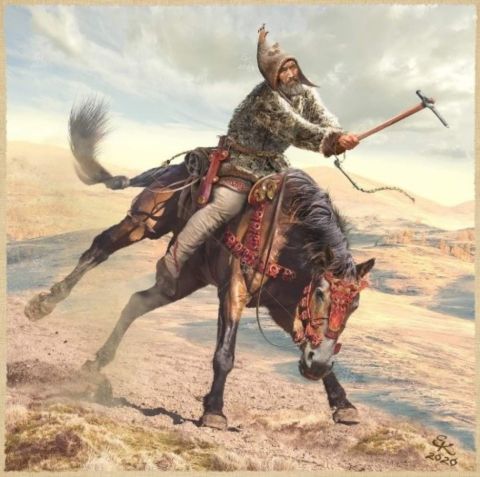

The ancient ancestors of the Hungarians had been nomadic cattle breeders. They had probably participated in trade exchange, served passing caravans, interacting with the southern regions, as evidenced by the Arab dirham coins in the burial ground; it is possible that the Magyars had performed robbery raids. Rare metal-plastic items, such as a bottle-shaped silver needle case, which is clearly of Prikamye origin, indicate the interaction of nomads with more northern regions.

During the excavation of the Magyar burial ground, SUSU archaeologists discovered the remains of three men aged approximately thirty, forty and fifty years. The death of one of the young men had been violent :there are approximately seven tetrahedral holes in the back of his skull, probably left in a combat clash with a cold weapon such as a chisel or a cleaver.

"Since such weapons were typical mainly for horsemen, it can be assumed that single blows were delivered with a chisel or a cleaver in pursuit of a running warrior," commented chief researcher of the SUSU Eurasian Studies Research and Education Centre, Professor Sergey Botalov. "And when he had already fallen to the ground, the blows were delivered with precision (which can be seen from the concentration of traces of blows in one place on the cranial vault) in order to finish off the man."

The death of the second young and third mature men had been natural, at least the scientists did not find any traces of violent death. Judging by the accompanying inventory, which consisted of a bow, arrows and melee weapons, the buried men had been warriors.

Today, within the framework of the RSF grant, researchers are also conducting anthropological work to reconstruct the appearance of the buried. The structural features of their skulls indicate an intermediate position of the early Magyars on the Caucasoid-Mongoloid vector of variability. According to special calculations, they have mixed forms with a predominance of the Caucasoid component and a conditional Mongoloid admixture (up to 30%). For two of the three skulls, Aleksey Nechvaloda, a research fellow at the Institute of History, Language and Literature (Ufa), performed graphic reconstructions of the men's appearance using the method of the famous Soviet archaeologist and anthropologist M.M. Gerasimov.